Joan Shelley Rubin, author of Songs of Ourselves: The Uses of Poetry in America, said the 1920s belonged as much to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow as it did to Thomas Stearns Eliot—and this is true.

The anti-Victorian, Imagism revolution of Bloomsbury, which gradually changed poetry from an art of song to an art of image through the ‘trickle-down’ effort of its elites, gained the overwhelming momentum of great numbers when its ‘trickle-down’ effort became normalized and taught in the academy–both in English departments and Creative Writing Workshops–during the second half of the 20th century.

Are there any prominent musicians who bother to set contemporary poetry to music?

The image in poetry became associated with art, while the music of poetry became associated with vulgarity.

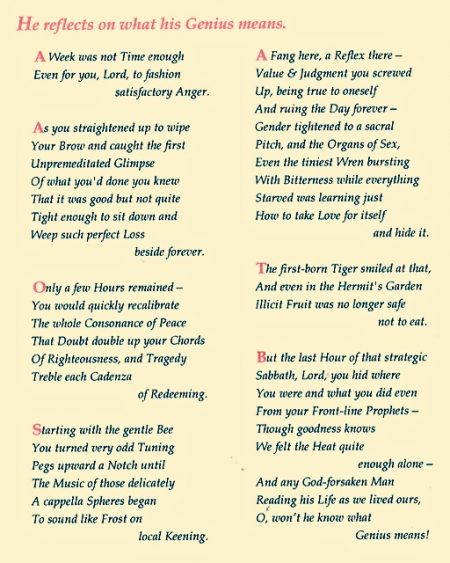

Two brief examples, from last century, will suffice:

First: these lines from J.V. Cunningham, the anti-modernist poet, who is largely forgotten:

How time reverses

The proud in heart!

I now make verses

Who aimed at art.

Second: Bloomsbury author Aldous Huxley’s infamous slam against Poe’s verse as “vulgar.” The prim Englishman’s distaste for musical Poe was quoted approvingly in Brooks & Penn Warren’s well-placed textbook, Understanding Poetry (first edition, 1938) which also solidified the reputations of Imagist classics, ‘At A Station In the Metro’ (Pound) and ‘The Red Wheel Barrow’ (Williams) in its unalloyed praise for these two works.

Could poetry change radically today? And, if it did, would the public even notice? The answer to both quesitons is, ‘no,’ and the reason the first answer is ‘no,’ is because the second answer is ‘no.’

How did poetry change so radically in the early part of the 20th century?

First, it did have a public, but not a particularly large or enthusiastic one, and secondly, poetry was understood by the public to have a certain definite identity: it looked like work by Longfellow and Tennyson.

An art whose practioners are disunited, who have no common expertise, will not be seen as an art at all. Poetry had a common expertise: the ability to compose memorable music with mere words, like Longfellow and Tennsyon.

“Verse is not easy,” Cunningham wrote. But the skill of verse is no longer a part of poetry; poetry no longer has a specific “skill.”

The Imagists never got beyond a very minor, little magazine existence, but they believed what they were offering would be very popular, like a portable camera; now you can just point and shoot! Anyone can appreciate images–and put them into simple poems–like haiku. Poetry for democracy! Poetry that was selfless and natural! It will be a phenomenon! But the public didn’t buy it–they still wanted their Tennyson and their Longfellow with their gadgets and their telephones and their cars. Imagism, like Futurism, Cubism and 12-Tone Music, failed to inspire anyone except the core of elites who were pushing them. Imagism was a flop.

Or, was it?

People ‘on the street’ today define poetry as vaguely expressive, and the public’s perception of something, we have learned, should not be underestimated. ‘Vaguely’ is the chief term here. No longer does the public think of poetry as Longfellow. They think of it as vaguely expressive.

100 years ago the American public had a more sharply defined view of poetry. It was like what those fellows, Mr. Alfred Lord Tennyson and Mr. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, wrote. That was what poetry was.

The zen joke of ‘The Red Wheel Barrow’ and ‘The women come and go/talking of Michelangelo’ resonated once, but these jokes are no longer funny. But Longfellow is gone, too.

Image truly belongs to other arts: painting, photography, and film; further, these arts do not need to look to poetry at all as they wrestle with the image.

Song belongs to songwriters, and songwriters, the good ones, are poets, but they are known to the world as songwriters; poetry’s identity carries on in the sister art of songwriting, and unlike the filmmakers, photographers and painters, songwriters do consult poetry, not contemporary poetry, but old poetry, the art, for inspiration.

Since poetry has given up song for image as its current identity, poetry manifests no contemporary attachment with any other art. No glory belongs to poetry, or is even reflected back on poetry. Poetry is in the dark.

Poetry, with no public identity, is stuck: it has nowhere to go.

History affords countless examples of technical changes which have improved music’s expressive qualities as a whole even as music, the art, remains, in its simplicity, recongizable to everyone. When the piano replaced the harpsichord, all composers took notice, not just some.

The modernist revolution changed poetry so that everyone took notice, but unfortunately in a way that made poetry no longer recognizable to everyone. Nor is it easy to say if expressive qualities have increased–certainly not in the public’s perception. As far as prose and how it perhaps opens things up, the problem poetry has, is that in prose, one would naturally think poetry could express itself with greater variety, but fiction owns prose, and poetry is expected to do something different than fiction; poetry as art has been developed in different ways than prose. Yes, poetry should be as good as good prose, and all that, but how does poetry keep from disappearing into it? And so poetry–sans the music that separates it from prose, as the art which the public knows as poetry–has been at sea for 100 years.

T.S. Eliot, an honorary Bloomsbury member, and the most respected critic of the 20th century, recommended minor poetry 300 years old as superior to major poetry composed 250, 200, 150, 100, and 50 years before his day. This, in some ways, was counter to the whole modernist revolution. John Donne? Andrew Marvell? Henry King, Bishop of Chichester? What was Eliot thinking? Eliot was thinking this: If my friends and I are to effect this modernist revolution of ours, we must not seem like mere brick-throwers; we need erudition, scholarship, appreciation of certain aspects of the past, and if we are to become professors and editors of modernist verse, it will be well to be able to make the past our clay, for revolutions must feed off the past; no revolution lives in the present day; Eliot knew he and Pound were not Bach, the master, at the keyboard, re-inventing music itself; he knew they were merely sullying a grand tradition with a little sleight-of-hand: Goodbye, Milton, Shelley, Poe, Shakespeare, Keats. Hello, Kyd, King, Corbiere. Eliot knew that when a revolution happens, the past will not disappear; a certain respect for the past must not only be feigned, but enthusiastically pursued, for every manifesto needs food; actual ‘new’ material (Waste Lands, cantos, wheel barrow haiku,) will run out in a week, so the past has to be transformed. Every revolution needs a professor; Mary Ann and Ginger alone will not do.

The image is free-standing and pre-verbal; it is not necessary for image to fit, or be coherent–it simply is. Why should such a thing be the essence of poetry? Ask that Bloomsbury elite. After a snort and a sigh and a sip of their very expensive wine, they will tell you.

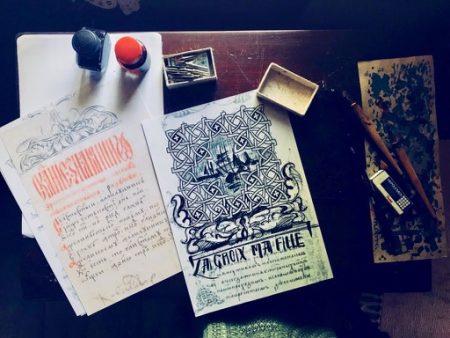

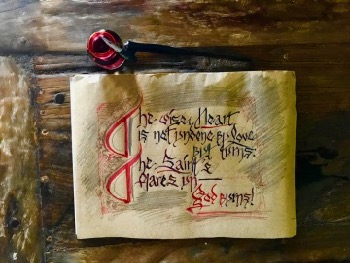

………………….[Click twice on the old script to read it more easily.]

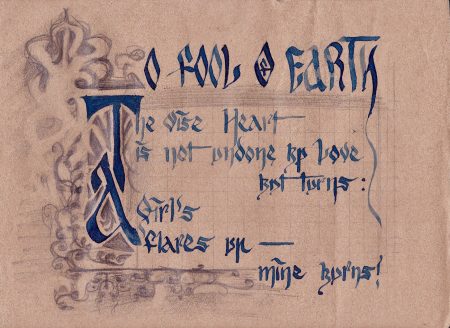

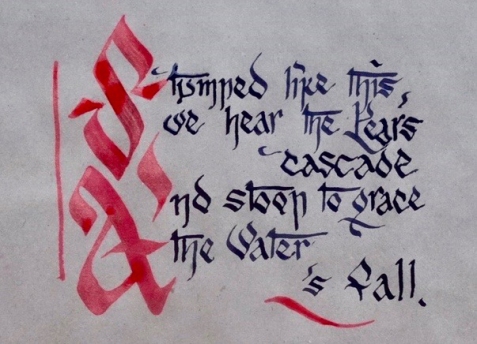

………………….[Click twice on the old script to read it more easily.] …………..[Click twice on both to see better, & read carefully for clues to decipher the text.

…………..[Click twice on both to see better, & read carefully for clues to decipher the text.